In an unusual case, the Ontario Ministry of Labour has charged a small town’s volunteer fire department with safety offences under the Occupational Health and Safety Act.

In an unusual case, the Ontario Ministry of Labour has charged a small town’s volunteer fire department with safety offences under the Occupational Health and Safety Act.

The case is of interest because it involves the Ministry of Labour using safety laws to scrutinize, through the courts, the actions of emergency response professionals who are faced with a crisis situation.

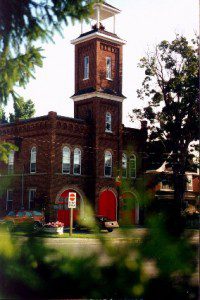

The charges arose from a restaurant fire in Meaford in September 2009. The air supply of one of the firefighters ran out while he was inside the building; another firefighter shared his air supply with him. They were rescued and substantially recovered from their injuries.

Although the MOL originally laid 6 charges, 3 were withdrawn prior to trial. The 3 remaining charges, all laid under the “general duty” clause of the OHSA, alleged that the fire department failed to activate an “accountability system to track firefighters entering a burning structure”; failed to maintain effective supervision by establishing a command post where radio transmissions could be heard by the incident commander; and failed to establish a Rapid Intervention Team for the protection of firefighters who may become lost or trapped.

The prosecution called 10 witnesses and then rested its case. The fire department then asked the court to dismiss all three charges before the Town was required to call its witnesses, on the basis that the Crown’s evidence – even if accepted as true – could not lead to a conviction.

Because all of the charges alleged a breach of the fire department’s “general duty” under the OHSA, and did not refer to any specific regulations under the OHSA, the court relied on “relevant guidelines”: the Guidance for Improving Health & Safety in the Fire Service which was prepared by the Ontario Fire Service Health and Safety Advisory Committee, a body established by the Ontario Minister of Labour under the OHSA.

The court dismissed the charge relating to the location of the command post, holding that, “None of the Crown’s witnesses testified that they believed, in any way, that the incident command was located at an inappropriate location. No alternate locations were suggested.” Similarly, the court dismissed the Rapid Intervention Team charge because “all witnesses who were asked about the RIT clearly testified that RITs were eventually set up . . . In this case, the particulars [of the MOL’s charge] allege that a RIT was not established. There is absolutely no evidence that would support this allegation.”

The court dismissed the charge relating to the location of the command post, holding that, “None of the Crown’s witnesses testified that they believed, in any way, that the incident command was located at an inappropriate location. No alternate locations were suggested.” Similarly, the court dismissed the Rapid Intervention Team charge because “all witnesses who were asked about the RIT clearly testified that RITs were eventually set up . . . In this case, the particulars [of the MOL’s charge] allege that a RIT was not established. There is absolutely no evidence that would support this allegation.”

The court did not, however, dismiss the charge which alleged that the fire department failed to set up an accountability system. The court stated that it was apparent from the Crown’s evidence ”that the Meaford Fire Department’s procedures as set out in [the Standard Operating Guidelines of the Meaford Fire Department] were not followed . . . [I]t is clear to the court that there is certainly some evidence which, if believed, could lead a trier of fact to conclude, beyond a reasonable doubt, that an accountability system was not properly activated . . .” The court permitted the MOL to proceed with that one charge.

Of the original 6 charges, the Ministry of Labour is now left with only one. It will be interesting to see whether the prosecutor decides to withdraw the remaining charge. If not, the trial will proceed with the fire department calling its witnesses in defence of the charge that it failed to set up an accountability system.

R. v. The Meaford and District Fire Department:http://canlii.ca/en/on/oncj/doc/2012/2012oncj113/2012oncj113.html

Source: Canadian Occupational Health & Safety Law (by FMC Law)

Discussion

No comments yet.